5:30

News Story

‘Meet people where they are’: Special teams aid Va.’s efforts to expand mental health care services

Mobile crisis units part of Virginia’s ever-expanding landscape of mental health resources

Editor’s note: The Mercury is not identifying the name of Asheley Tuck’s son to protect the child’s identity. Tuck’s statements were substantiated through interviews with mental health professionals with knowledge of her family’s situation.

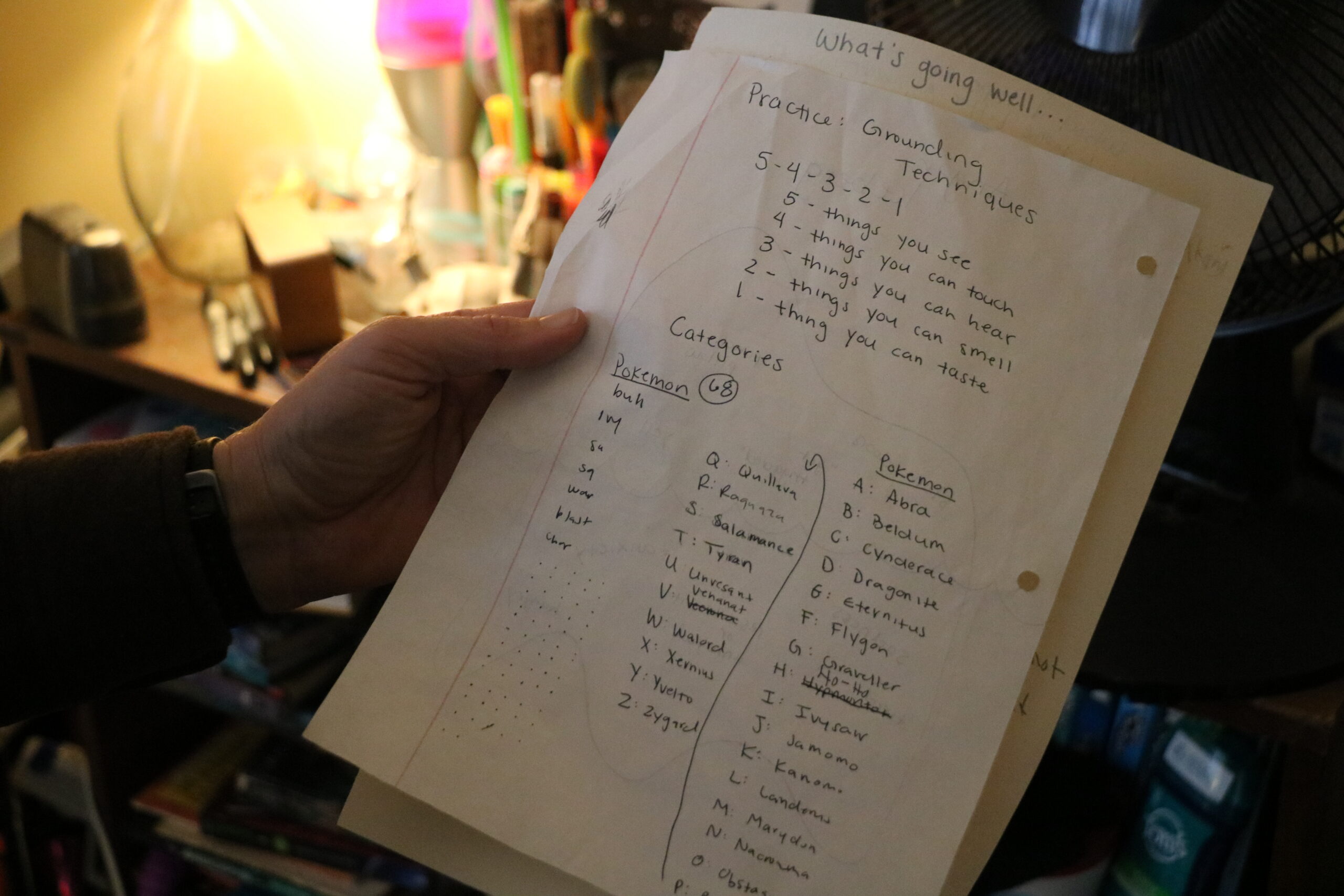

With books, toys and artwork strewn about, Asheley Tuck’s son’s room is the typical sort one might expect from an 11-year-old boy. What is less typical: a piece of notebook paper taped to his door labeled “safety plan.”

The paper outlines how sudden mood shifts, loss of interests, isolation or a racing heart could be warning signs of anxiety, so that he can better recognize when an attack might be coming on.

Tuck’s son also has notes that outline techniques — like listing types of Pokemon in alphabetical order — which can help him cope with swelling negative emotions.

The notes are relics from crisis response and follow-up counseling he received this past summer after he and some friends encountered an online predator during a sleepover.

Tuck said that she and her wife didn’t know how to best comfort their son when he called to be picked up from the sleepover and confided in them what had happened.

“(The person) scared them and asked them to do some things that were not appropriate for anyone, much less, you know, an 11-year-old,” Tuck said.

Her son expressed feeling like “his life was ruined” and he was worried he would be “plastered on the internet and what the repercussions would be,” Tuck recalled.

“He was devastated.”

Having known people who were social workers, Tuck realized she could call Richmond’s Crisis Response and Stabilization Team (CReST). Within less than an hour, a clinician arrived at their house to provide immediate counseling to the family. After the initial visit, CReST arranged follow-up visits for a few weeks and referred the family to additional counseling services if needed.

“The fact that he got services that quickly was a game changer for how he’ll be able to navigate his life going forward,” Tuck said.

While the clinician who responded to Tuck’s son was part of CReST through the Richmond Behavioral Health Authority, there are similar programs around Virginia, colloquially referred to as mobile crisis units. These professionals and teams are part of Virginia’s ever-expanding landscape of mental health resources and have played a role in keeping patients in their homes rather than hospitals or, in escalated cases, jails.

Clinicians on the scene

Erin DeLizzio, a program manager at CReST, explained that while some staff are located in the downtown Richmond office, others have take-home cars to be dispatched from around the region, from Hanover to Farmville to Emporia.

She said that her area, Region 4, was able to provide services to over 1,500 people in the 2024 fiscal year. Most of those people were diverted from hospitals and jails and were able to get help at their homes.

“You’ve got to be able to meet people where they are,” said Sen. Creigh Deeds, D-Charlottesville, a longtime champion for bolstering mental health resources in Virginia who supported the 2021 legislation that paved the way for mobile crisis units and other services.

CReST’s responses to calls for help can range from de-escalating situations over the phone to dispatching clinicians to meet with people directly. Sometimes patients need immediate counseling and connections to follow-up resources like therapists or psychiatrists. Sometimes they might need to be admitted to crisis receiving centers — which operate like emergency rooms in hospitals, but focus on mental health.

Clinicians can be dispatched when people call the regional mobile crisis line directly or when routed through emergency calls to 911 or 988, a national mental health crisis hotline.

When the national mental health emergency hotline transitioned to the easier-to-remember 988 system, Virginia legislation in 2021 funded expanded call centers and listed the deployment of mobile crisis units as part of 988’s responsibilities. The service has been on the rise in Virginia, which Gov. Glenn Youngkin has said he sees as a success because it means people are connected to resources before a crisis can escalate further.

Youngkin’s three-year Right Help, Right Now plan entails budget proposals from the governor and legislative actions by state lawmakers focused on mental health care. Youngkin recently celebrated the two year anniversary of the initiative.

“Right Help, Right Now is working,” he declared excitedly at a press conference on the two year anniversary of the initiative, Dec. 11.

The initiative’s bipartisan efforts build on a decade’s worth of work spearheaded by Deeds and the Behavioral Health Commission he helped establish. Outside of legislative sessions, the commission undertakes studies and hears from experts around the state to craft or endorse legislation.

Recent years have seen new solutions born from local tragedies.

A bill dubbed “Irvo’s Law” allows families access to their loved one if they are taken into custody by law enforcement during a crisis. Its inspiration stemmed from the death of Henrico resident Irvo Otineo, who died in a mental health hospital while constrained by law enforcement officers and staff, and whose mother was denied access to him there.

A 2020 law called the “Marcus Alert” stems from the death of Richmond resident Marcus-David Peters, who was killed by police in 2018 during a mental health crisis.

As a growing number of Virginia localities implement the law, it enables coordination between 911 and regional call centers to triage the best response from law enforcement and trained clinicians when handling mental health situations.

“A main goal is to not hospitalize someone if we can,” said Abigayle Hodges, a mobile crisis unit team leader at CReST.

Trying to keep the peace

Often, law enforcement officers are the first responders to crises and escort people to hospitals where they sit waiting with them. Other times, people may be subject to emergency custody orders, which is when a magistrate orders that someone needs to be evaluated by health professionals because they could be a harm to themselves or others.

Consensus has been building between some lawmakers and members of law enforcement that officers and deputies aren’t always the best people to take point or remain with people in crises for longer periods of time.

“Not only should there be less police interactions with someone who’s going through a crisis, but when you’re looking at rural areas such as the county where I’m from and small police departments throughout the region, then taking just one person off patrol can hurt a community,” said Tazewell County Sheriff Brian Hieatt.

A recent presentation to Virginia’s Behavioral Health Commission also noted how arrests of people in mental health crises have a “devastating impact” on those in crisis and that it can “stress local and state resources.” People in crisis can also be more prone to lashing out and assaulting an officer, regardless of their coherence or intent, and end up facing jail time as a result.

In his forthcoming budget presentation for 2025, Youngkin hopes that $35 million can be invested into creating “Special Conservators of the Peace,” he said this week. These are both armed and unarmed positions authorized by courts to carry out limited law enforcement duties.

While resources like 988 and mobile crisis units can help prevent people from going to the hospital, Youngkin believes the conservators can help improve the outcomes of those who are taken to hospitals by law enforcement.

“(Officers) are brought into many of these circumstances that not only distract them from so many other responsibilities, but then have an individual who’s in crisis enter the criminal justice system unnecessarily — we need to address both of those,” Youngkin said.

While state lawmakers will still need to collaborate with Youngkin throughout the first few months of 2025 to decide how the state’s budget will be allocated, Youngkin sees the conservator program as a temporary solution.

“We should see a reduction in hospital admittance, and therefore a reduction in the law enforcement needs around the hospital,” Youngkin said. “But for the time being, having our cops in place that allow this transfer of custody is really important.”

Anna Czaplicki Ryan, a program supervisor at CReST, described how some transfer of care is already happening between law enforcement and clinicians.

“A ‘warm handoff’ is the terminology we use,” she said.

CReST staff and law enforcement already have some experience working together in instances where police are at the scene of an emergency first and ask for assistance or for clinicians to take over care, Czaplicki Ryan explained. When officers and clinicians demonstrate the transfer of care to patients, it can help them feel supported and know they are “not abandoned.”

Deeds, who serves on the Senate’s finance committee, said that he’s “fine with” Youngkin’s conservator proposal.

“I just think that our focus should not necessarily be on the moment of crisis,” Deeds said. “Our focus also needs to be on prevention, on keeping people out of crisis.”

For Asheley Tuck, whose son experienced a trauma, she said that she’s glad she knew that 988 and CReST existed in their moment of need.

“If a friend had not mentioned that this program exists, I may not have known about it at all,” she said. “I think it should be regular public knowledge.”

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.