0:06

News Story

Pa.’s lack of progress a ‘600-pound gorilla that was ignored’ at bay cleanup meeting, conservation group leader says

OXON HILL, Md. — The Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s president blasted the silence surrounding Pennsylvania’s failure to live up to its commitments to cut pollution flowing into the Chesapeake Bay Thursday at a meeting of the Chesapeake Bay Executive Council.

“There was a 600-pound gorilla in the room that was ignored until it was brought up by the media,” said William C. Baker, the foundation’s president. “I don’t call that leadership.”

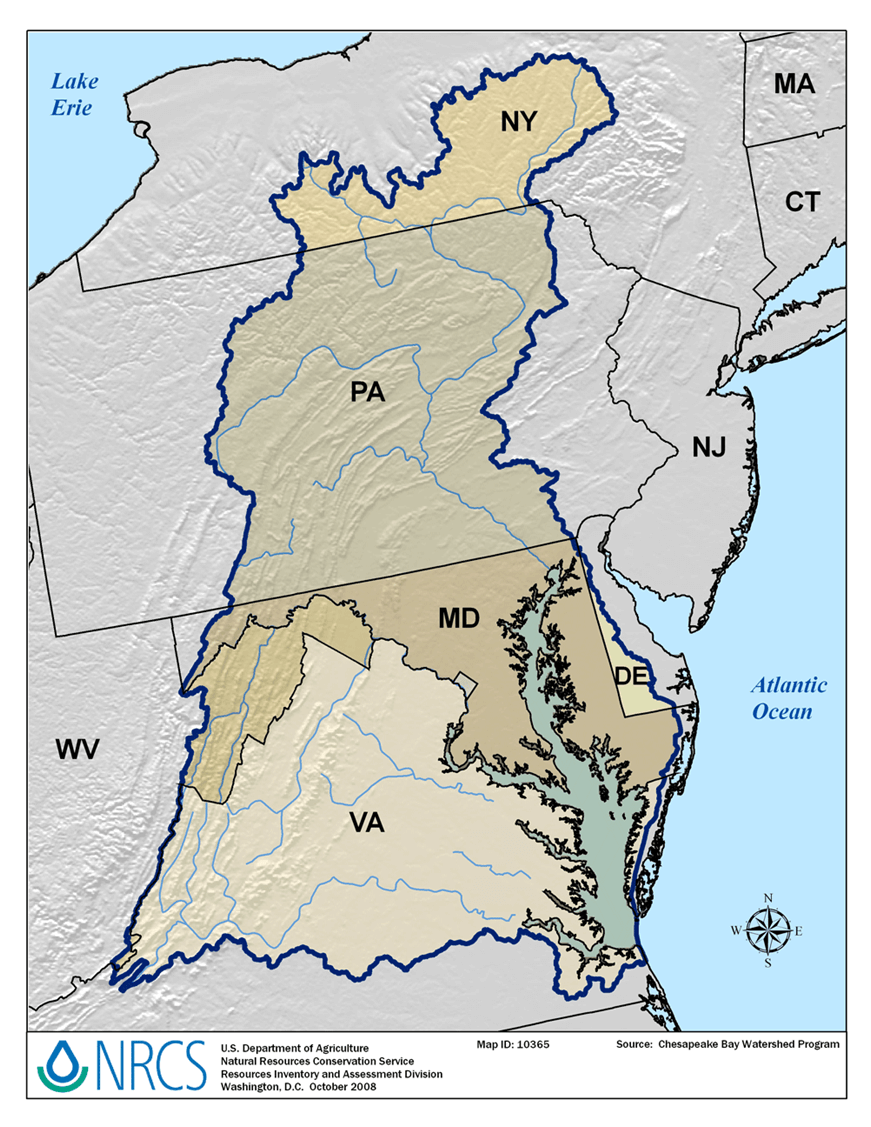

The foundation says Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania account for 90 percent of the pollution in the bay and that Pennsylvania’s “lackluster efforts are threatening years of progress under the collaborative cleanup agreement established in 2010.”

Virginia Gov. Ralph S. Northam (D) was the only other state chief executive besides Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, a Republican, to attend Thursday’s annual meeting in Oxon Hill of the council, which Hogan leads and consists of leaders from the six Chesapeake Bay watershed states and the District of Columbia.

Northam, who spoke, as he often does, about growing up on the Eastern Shore and considering the bay “literally my backyard,” touted an “environmental literacy” summit that his wife led earlier this year and said the state was seeing real progress with a higher grade of crab, more oysters and more subaquatic grasses.

Northam said he still worried about the state’s striped bass population and that his administration had enacted enhanced protections.

“I’m proud that we have developed a bold and comprehensive roadmap for success,” he said.

Northam took gentle jabs at other bay states. Thanking Hogan for the crab cake lunch the officials ate before the formal meeting, he noted, “These crabs originate in the water of the Chesapeake Bay down in Virginia. [Hogan] says that when they get older and wiser, they move up to Maryland. I say they don’t think as clearly.”

Northam also pointed out that 22,000 Pennsylvanians purchased saltwater fishing licenses in Virginia last year, and that one in 12 tourists on the Virginia coast come from New York.

Northam expressed confidence that the EPA would closely scrutinize the states’ bay cleanup proposals and would “take action” if necessary. But Baker, of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, expressed fears that the EPA was unprepared to force states – especially Pennsylvania – to meet their commitments.

“If we don’t get any action from EPA we’re going to have to evaluate our options,” he said.

Hogan sought to downplay any animus between his state and Pennsylvania over Chesapeake Bay cleanup efforts – a week after blistering the Keystone State in a letter to federal and commonwealth officials.

“I wouldn’t really describe it as a tiff,” Hogan said in response to a reporter’s question. “I think we’ve had very productive discussions today. I do think they’re doing everything they can. …They’re good neighbors.”

In his letter last week to Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf (D) and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Andrew Wheeler, Hogan complained bitterly that Pennsylvania was falling short of its requirements to reduce nitrogen in state waterways and had a $320 million funding gap to meet federally mandated cleanup goals.

The six states in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, along with the District of Columbia, submitted final bay cleanup plans to EPA in late August, outlining their commitments through 2025. Representatives from each of the jurisdictions summarized their proposals at Thursday’s meeting.

Asked by a reporter about Pennsylvania’s so-called Watershed Implementation Plan, Wheeler said EPA officials would need a couple of months to evaluate each jurisdiction’s goals and were prepared to follow up if they found deficiencies.

“I’m not going to prejudge those proposals,” he said.

But Baker expressed skepticism that the industry-friendly Trump administration EPA, which has scaled back numerous environmental regulations, was equipped to provide sufficient oversight of the states’ plans.

“How can they say that they’re going to get the job done when they don’t even express concern about an acknowledged $320 million shortfall?” he said.

Representatives boasted about the efforts each of their states are making to help clean up the Chesapeake Bay, and many lauded the sense of collaboration among the states. But each state has its own unique relationship with the bay – and residents of upstream states are sometimes unaware that they even have an impact on the bay’s health, blunting those states’ sense of urgency.

“If the water in the Chesapeake Bay were as good as the water quality when it leaves New York, the Chesapeake Bay would not be impaired,” said James Tierney, a deputy commissioner at the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

Patrick McDonnell, secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, said the commonwealth under Wolf was spending record amounts of money to clean up its waterways.

“The state of Pennsylvania is committed to implementing our plan and getting there by 2025,” he told his colleagues. “Pennsylvanians value the water resources that we have.”

But McDonnell suggested that waterway cleanup is designed to benefit Pennsylvania first and foremost. He said that effort would benefit from the first-ever Pennsylvania farm bill that passed recently, which includes agricultural conservation funding.

“We have a sense of ownership of the challenge of improving water conservation … but there’s an understanding that more needs to be done,” McDonnell said.

In a brief interview, McDonnell acknowledged that “other states have concerns” about Pennsylvania’s ability to fund its bay cleanup mandates. But, he added, “I know some of the other states have concerns about their own funding.”

But Hogan, who was re-elected to serve another year as head of the Chesapeake Bay Executive Council, expressed satisfaction with all the states’ progress.

“The goal of clean water is truly within our sights after three or four decades of collaboration,” he said.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.